Mississippi River Lighthouses and Lightships- Lighting the Mississippi River Passes Post La Balize

Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the increasing role of New Orleans in the economic development of the nation, marine commercial and passenger traffic in the Mississippi River via the Gulf of Mexico experienced a significant surge. Until about the 1820’s when steam powered vessels and sailing vessels with steam auxiliary power were beginning to be produced in significant numbers, the ships carrying cargo and passengers were exclusively sailing vessels. Irrespective of the type of vessel, navigation of the complex “Bird’s Foot Delta” of the lower Mississippi River became increasingly important and critical. As described in the previous brief, the Spanish were perhaps the first to address this need by their installation of the La Balize lighthouse on Northeast Pass that would guide vessels into the Southeast Pass and ultimately to the mouth (defined as located at the Head of Passes) of the Mississippi River and thence to New Orleans. One of the significant challenges to both the mariners and officials wanting to facilitate the safe passage of vessels to and from New Orleans was the ever-changing conditions, principally the depth, along the Mississippi River delta passes. As you will note as you continue to read, lighthouses provided on certain passes (e.g., Pass-a-Loutre and Northeast Pass) became ineffective due to shoaling of the waters of the passes. In another instance, the installation of jetties along South Pass actually caused the waters in the pass to deepen thus opening the pass to vessel traffic.

Lighthouse builders and keepers faced at least two additional significant challenges: (1) the relatively rapid deterioration of wood structures and (2) the poor foundation conditions of the alluvial soils in the Mississippi River delta. The latter challenge was exacerbated by a lack of knowledge about the principles of geotechnical engineering (soil mechanics and foundation engineering) at that time. By definition, geotechnical engineering is the study of the behavior of soils under the influence of loading and soil-water interactions. Among other applications, geotechnical engineering principles are applied in the design of building foundations, embankments, retaining structures, and earth dams. Probably one of the earliest textbooks printed in this field was that of Jacoby and Davis in 1914, Foundations of Bridges and Abutments, First Edition. The first comprehensive book on soil mechanics was not published until 1943, Theoretical Soil Mechanics by Karl Terzaghi and it wasn’t until 1948 that Karl Terzaghi and Ralph Peck co-authored, Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice. Given the dates of those seminal publications, most of the lighthouse installations at the Mississippi River passes preceded a fundamental knowledge and understanding of geotechnical engineering principles and applications by 70-120 years! It’s no wonder that lighthouses continued to be plagued by problems attributable to unsatisfactory foundation systems. However, one could question the fact that lighthouse builders continued to employ foundation systems similar to those that had previously failed.

Another question-could the transition from wood or brick masonry to cast iron for lighthouse construction been made sooner than the Southwest Tower of 1873? It should be noted that Congress had actually allocated $45,000 in 1854 to replace the failing Southwest Pass lighthouse with an “iron screwpile tower” but circumstances including the Civil War had delayed construction until 1873. Whereas cast iron was used as a construction material as early as 1781 for The Iron Bridge in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, England, its competitive cost, and suitability for a variety of uses didn’t materialize until somewhat later owing to refinements developed during the Industrial Revolution. By the mid-19th Century, cast iron was considered to be a common structural material. So, the answer to the question posed earlier is probably yes but the lag time was comparatively short- 20 years or so. Interestingly, it has been reported that in 1847 the “collector at New Orleans requested that the third South Pass Lighthouse be an iron lighthouse.” However, his request was not accepted, and another wood lighthouse was constructed. Had his request been granted, it might have led to an earlier transition to the use of cast iron as the principal lighthouse construction material in the Mississippi River passes. A material much stronger and more resistant to deterioration than timber.

Following the development of shoaling of the Pass-a-Loutre and Northeast Passes, the primary focus of lighthouse development centered almost simultaneously on both the South and Southwest Passes. The South Pass became viable because the installation of a system of jetties at the pass that was completed in 1879 by James Buchanan Eads caused scouring that created adequate draft in the pass for both commercial and passenger vessels. It might be noted that Eads designed and built the Eads Bridge, the first Mississippi River bridge south of the Missouri River. Completed in 1873, the bridge still stands and carries traffic to this day! The bridge pioneered the use of steel rather than wrought iron as a construction material.

The lighthouse development period beginning around 1830 and ending late in the century became somewhat chaotic for a variety of reasons including foundation failures, storms and flooding, wood structure deterioration, and the Civil War. The following tabulation attempts to document lighthouse development at the South and Southwest Passes during this period. As you will note, there are gaps in the information I was able to locate in my research efforts.

Further, occasionally, different sources sometimes cited conflicting information and dates. I’ve tried to present what I judge to be the best and most accurate consensus-based information possible, but I don’t warrant its total validity.

As indicated in the tabulation, fairly shortly after the completion of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse on Northeast Pass, efforts were initiated to construct lighthouses on both South and Southwest Passes. The exact motivation for this action is not evident but it could have been based on the actual usage of the passes by mariners. Shoaling was one of the principal concerns in each of the passes, but essentially no data are available to judge the variation of drafts in the passes with time. A variety of vessels of varying drafts used the passes and it’s conceivable that the captains of those vessels selected the pass that they knew to have adequate depth for their vessel. To some extent, vessel type dictated the draft of the vessel, but significant variations were possible. A review of the data provided by the HathiTrust Listing of Ship Registers and Enrollments in New Orleans, 1821-30, gives some insight into the range of drafts for various classes of vessels. As a class, schooners generally exhibited comparatively shallow drafts but drafts as great 8-ft. were possible. Ships generally exhibited the largest drafts, as great as almost 15-ft. Drafts in the range of 7-13 ft. were reported for Brigs. Steamboats tended to exhibit the greatest variation in drafts, ranging from a minimum of 3’ 10” to a maximum of 10’ 11”. For a pass to accommodate any vessel choosing to use it during the 19th Century, a minimum depth in excess of 15-ft would be required.

Few details concerning the first lighthouse at South Pass were found. However, it is believed to have been a masonry tower with a painted black band to distinguish it from the planned lighthouse at Southwest Pass. It was also distinguished by its flashing light produced by seven lamps and reflectors on either side of a revolving chandelier. It is reported that the builder, Winslow Lewis, planned to drive piles for the lighthouse’s foundation but was persuaded by a New Orleans official to “float” the foundation on a cross-hatched mat of timbers. Such a system might have worked had not flooding caused logs being carried by the river’s current to knock the tower off its foundation in 1839. Two wood towers followed, both of which fatally deteriorated, the first in 5 years and the second in 19 years and had to be replaced. The 1848 replacement lighthouse (shown here) featured an octagonal tower emanating from the roof of the keeper’s quarters.

Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War, Confederate forces removed the lighthouse lens and oil from the station, but the lighthouse was returned to service by Union forces in the Fall of 1862. Despite being classified as seriously deteriorated in 1867, the lighthouse was not replaced until 1881. In 1875 and in advance of construction of the new lighthouse, James Buchanan Eads began construction of a parallel system of jetties that extended into the Gulf. The consequence of this action was to produce scouring that deepened the pass to 30-ft. or so, a depth that could accommodate any vessel operating at that time. In advance of the installation of the jetty system, it was reported that the pass had shoaled to only 6-ft. By significantly increasing shipping access to New Orleans, the port went from the ninth largest port to the second largest port in the U. S.

The replacement lighthouse, completed in 1881, was a 105-ft. hexagonal cast iron skeletal tower. Unlike all the previously constructed lighthouses, soil borings were made to determine the properties of the underlying soils. The resulting data were used to design and then construct a suitable foundation, a task that took some 4 months to complete. As noted in the tabulation, this tower still stands today.

A lightship (LV-43) was stationed at South Pass during the winter months from 1894-1912. Its purpose was to provide guidance to mariners “when a thick cloak of “sea smoke” (Cipra, 1997) developed. In 1912, although LV-43 was nearing the end of its useful life, it was transferred to Southwest Pass where it remained until 1917 at which time it was replaced by Lightship LV-102 (shown here). LV-102 only remained on station at Southwest Pass for several months. Improvements in navigation aids at Southwest Pass precluded the need for a lightship. LV-102 was then transferred to South Pass and remained on station until 1933 at which time its purpose was replaced by modern navigation aids.

Within essentially the same timeframe as the lighthouse development efforts at South Pass, lighthouse construction and replacement activities were underway at Southwest Pass. Similar to the initial brick masonry conical tower at South Pass, an almost identical tower was constructed at Southwest Pass. The original and replacement tower at Southwest Pass suffered the same fate as the first tower at South Pass; that is, failure by some combination of sinking, tilting or complete toppling. Note the photo showing the tilting of the tower completed in 1839.

In 1861, Confederate forces stole the lighthouse lens and other property deemed of value from the second lighthouse installation. However, the U. S. fleet subsequently took possession of the lighthouse and installed a fourth-order lens in 1863. Likely, it was understood that such an action represented only a temporary fix to a serious problem and that a more permanent solution was needed. Such a permanent solution was decided to be a 128-ft. cast iron skeletal tower. Completed in 1871 and after functioning satisfactorily for almost 20 years, a fire temporarily interrupted the lighthouse’s service. Being critical to navigation, the lighthouse was restored to service within a month. The situation at the pass remained more or less static until 1929 at which time a station with the principal function to serve as a foghorn was placed on the east jetty. While awaiting funding for the east jetty station, a lightship was anchored off the pass; LV-43 from 1912 to 1917 and LV-102 from 1917 until its discontinuation in 1918.

In 1953, the east jetty station was upgraded to full lighthouse status. Shown in the photo (below left) are the iron skeletal tower completed in 1871, three keeper’s residences completed in 1909, and, in the upper right-hand corner, the remains of the 1839 tower. This tower continued to serve until it was replaced by a complex resembling an offshore oil platform (below right) in 1965. That complex was demolished in 2007 and replaced with a three-legged skeletal steel tower.

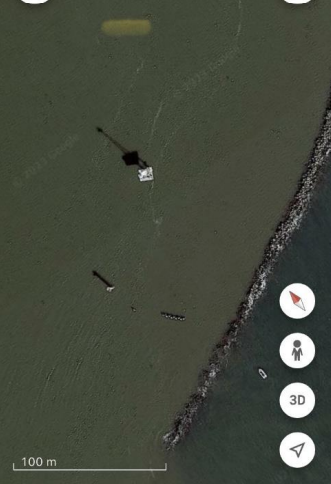

This is an image I made using Google Earth showing the current lighthouse tower near the east jetty at the entrance to Southwest Pass. You can get some sense of the configuration of the lighthouse tower by its shadow. Southwest Pass has been considered the main shipping channel in the Mississippi River Delta since 1853.

A subsequent brief will identify and describe lighthouses and lightships located west of the Delta but still in Louisiana waters.

Author’s Note: Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the brief. However, some inconsistencies were encountered between the various reference sources, mainly in terms of dates. In my judgment, these discrepancies do not detract from the monumental efforts of 19th and 20th Century legislators, officials, and builders to provide mariners with the guidance needed for safe passage into the Mississippi River in route to New Orleans.

Sources:

Cipra, Donald L., Lighthouses, Lightships and the Gulf of Mexico, Cypress Communication, Alexandria, VA, 1997

South Pass Lighthouse, Louisiana at Lighthousefriends.com

South Pass Lighthouse > United States Coast Guard > All (uscg.mil)

Port Eads, Louisiana - Wikipedia

Southwest Pass (1871) Lighthouse, Louisiana at Lighthousefriends.com

Southwest Pass Lighthouse > United States Coast Guard > All (uscg.mil)

Lightships of the United States Government: Reference Notes - Willard Flint - Google Books

Ship Registers and Enrollments of New Orleans, Louisiana, Survey of Federal Archives in Louisiana, Division of Community Service Programs, Work Projects Administration - Volume 1, August 1941; Volume 2, February 1942; Volume 3, March 1942; Volume 4, March 1942; Volume 5, March1942; and Volume 6, March 1942. (Note: Access to copies of these volumes is available on The Digital Library of the HathiTrust.)