Naval Battles of the Civil War-Lower Mississippi River 1861-62

The focus of this brief will be the two Civil War naval battles that took place at locations along the lower Mississippi River. One of these battles proved to be pivotal to the Union forces in seizing and maintaining control of the Mississippi River.

The first shots of the naval war and the first battle of the Civil War took place at Fort Sumter, near Charleston, South Carolina, on April 12-13, 1861. The Fort, under control of Union forces and commanded by Major Robert Anderson, surrendered after being bombarded by Confederate gunfire for over 34 hours. Surprisingly, there were no Union fatalities from the bombardment. The Confederate forces, under the command of Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard, operated principally from land-based fortifications although one reference cited the existence of “floating batteries.” The only ship mentioned being involved in the action was the Union supply ship, Star of the West, that was driven away by Confederate gun fire in advance of the battle.

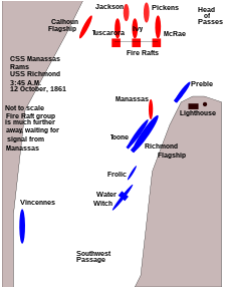

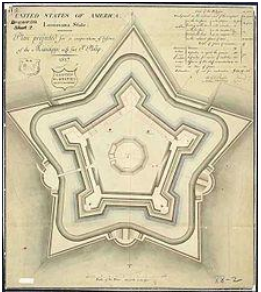

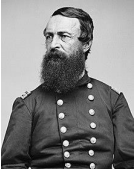

The first relevant naval battle within the framework of this brief is the Battle of the Head of Passes or, alternatively, the Battle at the Southwest Pass of the Mississippi River, October 12, 1861. Head of Passes, as illustrated in the following diagram, is located at the confluence of the three main passes of the Mississippi River. The Union fleet was basically stationed at that location to achieve a blockade of New Orleans. It was also an advantageous location from which to mount an attack of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, both of which were located in Plaquemines Parish more or less opposite of one another on the River. The Union fleet was composed of four vessels: USS Richmond, a screw sloop with more firepower than the entire Confederate fleet in the area; two sail-powered sloops of war, the Vincennes and Preble; and Water Witch, a steam-powered side wheel gunboat. The principal purpose of the Water Witch was to provide towing capability for the Vincennes and Preble should the winds and/or current prove to be unfavorable. Commanding the Union fleet and captain of the USS Richmond was Captain John Pope.

Commanding the Confederate naval fleet at New Orleans, dubbed the “mosquito fleet” by the local media, was Commodore George N. Hollins, a US Navy veteran. Under his command were six lightly armed riverboats: Tuscarora; McRae; Ivy; the flagship Calhoun; Jackson; and Pickens. To this fleet was added the CSS Manassas, an ironclad ram privateer commandeered at gunpoint.

The Confederate fleet’s attack on the Union fleet was mounted after moonset, October 12, 1861. The USS Manassas was to lead the attack and set her sights on ramming the USS Richmond with the objective of critically damaging her after which a fire raft would be pushed forward by each of the Confederate vessels- Tuscarora, McRae, and Ivy, and into the ships of the Union fleet. Whereas the CSS Manassas did ram the USS Richmond, the impact of the attack was mitigated by the USS Toone (a coal tender for the Richmond) moored alongside the Richmond. Further, the impact critically damaged one the two engines of the Manassas causing her to limp back upstream, no longer a factor in the attack. The fire rafts also proved to be a non-factor in the attack, but the Union fleet was driven off by the longer-range fire capabilities of the rifled cannons of the Tuscarora, McRae and Ivy. In spite of not having inflicted any major damage to the Union fleet or casualties to its sailors, the success in forcing the Union fleet to withdraw was considered at the time to be a major Confederate naval victory and an embarrassment to the Union Navy. The only tangible spoil from the battle was the capture of the Toone and its supply of coal. However, as a ship, it was not considered worthy of refitting for use by the Confederate Navy.

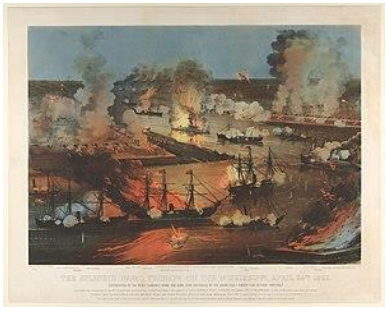

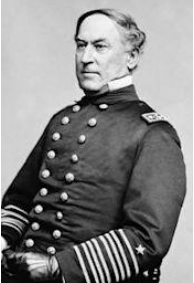

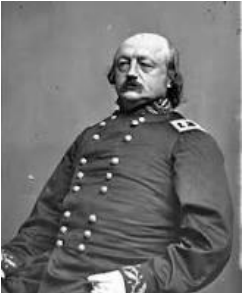

After the Union Navy’s debacle in the Battle of the Head of Passes, based on the recommendation of his adoptive brother D.D. Porter to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Gus Fox, the Union Naval Flag Officer David G. Farragut was charged with the task of organizing the West Gulf Blockading Squadron with the objective of re-establishing an effective blockade of the Mississippi River and attacking New Orleans. To this end, he was sent to the Mississippi River delta with a significant force that would ultimately engage with Confederate forces in what has been termed the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip (shown here). This battle (depicted above), waged during the period April 18-28, 1861, is considered to be the decisive battle for the possession of New Orleans during the Civil War. The forts, located near a bend of the River some 25 miles north of Head of Passes, brought some 177 guns to bear at a location on the River that would cause vessels to slow as they negotiated the bend. Countering the Confederate forces arrayed in the forts was a massive Union naval force consisting of six ships, 12 gunboats and 26 mortar schooners. Mortar schooners (shown left) were normally equipped with 13-in mortars that could lob projectiles over the walls into the interiors of the forts with devastating effect. Pictured here, David D. Porter (a Commodore at the time of the Battle and later promoted to the rank of Admiral) commanded the somewhat independent mortar schooner force. Interestingly, the Porter family fostered David Farragut after the death of his mother when he was 7 years old. Thus, Farragut was the adoptive brother of Porter. In the attack on the forts, the naval forces of the Union were supplemented by a ground force of some 18,000 under the command of Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler. However, according to Cavell, Farragut delayed Butler’s forces from attacking the forts until his naval forces had managed to proceed past the forts.

In addition to the forts, a shore battery was located on the eastern bank of the river more or less directly opposite Fort Jackson. It was at that location that barriers was stretched across the river to stop the advance of Union naval forces at least temporarily. Actually, two barrier systems had been deployed initially- a log and chain and four boat hulls linked together by chains. The former system had actually washed away due to the accumulation of debris from upstream. Confederate naval forces consisted of two ironclads- CSS Manassas and Louisiana; two converted merchant ships- CSS McRae and Jackson; two ships provided by the State of Louisiana- General Quitman and Governor Moore; six cotton-clad rams of the River Defense Fleet- Warrior, Stonewall Jackson (shown here), Defiance, Resolute, General Lovell and General Breckinridge; and several tugs and unarmored harbor craft- Belle Algerine and Mosher. The CSS Louisiana was reported to have been ”non-operational” and had to be towed into position. A third ironclad, the CSS Mississippi was still being completed and was situated in the shipyard where it was ultimately destroyed.

The Union fleet assembled at Ship Island in the Mississippi Sound and then moved to positions near the forts on April 14th, but it wasn’t until April 18th that the mortar schooners initiated action. During this period of bombardment, specifically on April 20th, Farragut ordered one of his officers to undertake a mission to break through the barrier. That officer was Henry Bell who in command of the USS Itasca and USS Pinola was able to unlink chains connecting several of the hulls in the barrier. This action did not completely eliminate the chain barrier but opened approximately a 400 ft. wide gap on the eastern side of the river that allowed the Union fleet to proceed upriver. While the bombardment of the Confederate forts was judged to be largely ineffective, it probably did provide a distraction that allowed most of the vessels under Farragut’s command to proceed up the river on April 24th to positions north and out of range of the guns of the forts. In a last-ditch effort to repel the US Naval fleet, the Confederate forces directed fire barges into the US Naval fleet. One fire barge managed to set Farragut’s flagship, USS Hartford, on fire but for the heroic efforts of the crew to douse the fire would have been a devastating loss. This engagement was not without consequences to both fleets but of the two, the Confederate fleet losses were the more devastating. Essentially all of the Confederate gunboats were either sunk or neutralized. On the Union side, one gunboat was lost and three turned back with undetermined losses and damage. Given the extensive losses suffered by the Confederate fleet as well as the failure of the Confederate government to provide additional defenses south of the city, the Union fleet proceeded undeterred to capture the City of New Orleans. There is some evidence to suggest that Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet believed that the major threat to the city was upriver rather from the south. This belief or miscalculation led to an inadequate defense system being provided south of the city. While the Confederate forts survived the attack, the forces at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 28th thus causing the surrender of the fort. Somewhat later, Fort St. Phillip was also surrendered. To avoid capture and use by the Union, the CSS Louisiana was blown up as well as the Confederate fleet patrolling Lake Pontchartrain. One very important consequence of the surrender of New Orleans, was the decisions of both England and France to not diplomatically recognize the Confederacy. It certainly undermined the prospect of a potential negotiated settlement with the US government that would allow the Confederacy to remain in place and be supplied militarily by England and France. However, the extent to which those decisions actually impacted the Confederate war effort is unclear. Historians who have studied this encounter between Confederate and Union naval forces attributed the defeat of the Confederate forces to a variety of factors. One historian (John D. Winters) attributed the defeat to “Self-destruction, lack of cooperation, cowardice of untrained officers, and the murderous fire of the Federal gunboats…” Another historian (Allen Nevins), argued that “the Confederate defenses were defective.” Among other factors, he concluded that “Confederate leaders had made a tardy, Ill-coordinated effort to muster at the river barrier.”

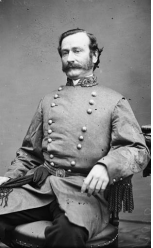

Once having passed the forts and defeated the Confederate fleet, a Union fleet of fourteen vessels proceeded upstream to New Orleans arriving in the afternoon of April 25th basically placing the City under the threat of attack for which it had no defense. The Confederate troops that had been stationed there had been withdrawn by their commander, General Mansfield Lovell (shown left). Given these circumstances, Farragut demanded that the City surrender, a demand that the Mayor and Council deferred to Lovell. However, having basically abandoned the City, Lovell deferred the decision back to the city officials. Three days of fruitless negotiations followed after which Farragut sent a delegation of officers, soldiers, and marines ashore to remove the State flag from the Customs House and replace it with the flag of the United States. That action on April 28th basically ended the stalemate and ultimately placed New Orleans under the Federal commander, Major General Benjamin Butler (shown right). Butler was reported to have administered the affairs of the City in a “tactless manner” that only exacerbated the hostilities between the North and the South. Butler remained in that position until December 14, 1862, at which time he was replaced by Major General Nathaniel Banks. Counter to some accounts, this change was not attributed to the way in which Butler had administered the City. On the positive side, the manner in which New Orleans was captured spared the city from the devastation of its historic structures and the loss of life. In addition, Butler is given credit for comparatively quickly getting businesses and the port back up and functioning again. By signing an oath of allegiant to the United States, residents were allowed keep their property and go “about their business as usual.” Free to operate on the waters of the Mississippi River without any further Confederate resistance, Farragut ordered expeditions to the north that resulted in the surrenders of the Confederate forts at Baton Rouge and Natchez. However, at Vicksburg, the guns of the Union fleet could not reach the Confederate defenses located on the bluffs of the city. This caused Farragut to initiate a siege strategy as a means to capture the city. Unfortunately, this approach proved to be ineffective when falling river levels forced Farragut to abandon his position. Vicksburg did not fall until a year later. The defeat of the Confederate forces at Forts Jackson and St. Phillip effectively ended its control of the Mississippi River and New Orleans. While devastating to the Confederate war effort, the manner of capture of New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Natchez spared not only the residences and infrastructures of those cities but saved countless lives.

Sources

Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Phillip, Wikipedia Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip - Wikipedia

David Farragut, Wikipedia David Farragut - Wikipedia

David Dixon Porter, Wikipedia David Dixon Porter - Wikipedia

Benjamin Butler, Wikipedia Benjamin Butler - Wikipedia

Mansfield Lovell, Wikipedia Mansfield Lovell - Wikipedia

George N. Hollins, Wikipedia George N. Hollins - Wikipedia

Acknowledgement

The significant contributions of Dr. Samantha Cavell, Assistant Professor of Military History, Southeastern Louisiana University, to the content of this brief are gratefully acknowledged. Dr. Cavell also provided the following listing of reference sources concerning the relevant Mississippi River Civil War naval battles.

Lincoln’s Trident: The West Gulf Blocking Squadron during the Civil War. Robert M. Browning, Jr., University of Alabama Press, First Edition, 2015.

The Civil War on the Mississippi. Barbara Brooks Tomblin, University Press of Kentucky, 2022.

The Mutiny at Fort Jackson: The Untold Story of the Fall of New Orleans (Civil War America) Michael D. Pierson, The University of North Carolina Press, Reprint Edition, 2009.