Early Explorers of the Gulf, Basin, and the Mississippi River - Part B

This second part of the brief on early explorers deals principally with explorers whose expeditions focused on the Gulf, its surrounding lands or the Mississippi River. For completeness, it includes a summary of the explorations of d’Iberville and d’Bienville but a detailed discussion of their efforts will be addressed in a future brief.

1519- Alonzo Alvarez de Pineda has been reported to be the first to explore the Gulf of Mexico in 1519. Pineda, a Spanish conquistador, and cartographer led a Spanish expedition that explored the boundaries of the Gulf extending from the west coast of Florida to the coast south of the Yucatan Peninsula. He was first to produce a map of the Gulf. Albeit crude and qualitative, the map does with reasonable accuracy depict the essential features of the shoreline of the Gulf. Superimposed upon a copy of de Pineda’s original map are typed labels of several prominent features. It is noted that Florida is correctly shown as a peninsula rather than as an island as it was initially thought to be by Ponce de Leon.

1527- Panfilo de Narvaez lead a Spanish expedition to colonize and establish garrisons in La Florida. The expedition is believed to have landed in Boca Ciega Bay, some 15 miles north of Tampa Bay. As the expedition moved northward along the west coast of La Florida, Narvaez divided his contingent into two parts- one proceeding by land and one proceeding by water. Despite the intention that these contingents reunite at a “major harbor” to the north that didn’t occur because the assertion of a major harbor was not true. The land-based portion of the expedition experienced significant hardships including attacks by indigenous tribes, starvation, and sickness. Desperate, the expedition decided to build boats and travel westward along the northern Gulf Coast to Mexico. The expedition successfully navigated most of the journey before being cast upon an island near the present-day Galveston Island by a major storm. Out of the 300 men originally a part of the land-based expedition, only 80 still remained following this event. These men were captured and made slaves by indigenous nations. After 8 years, only four members of the original expedition survived among which was Cabeza de Vaca who would return to Spain and publish a book about the expedition including the indigenous people, wildlife and flora and fauna of inland areas. Take a close look at the inset diagram in the upper left-hand corner of the map. You can clearly see a representation of the Mississippi River passes, the most prominent of which is the southwest pass.

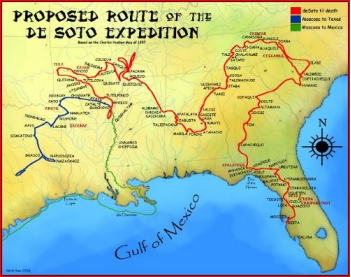

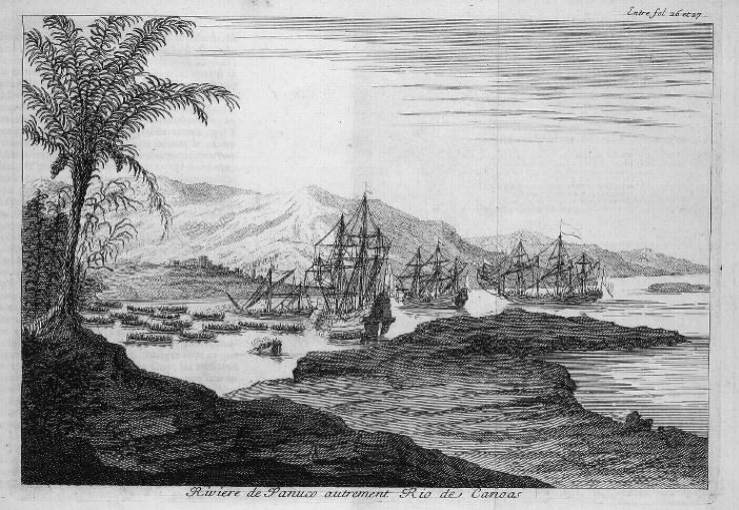

1541- Hernando De Soto was the first European documented to have seen and crossed the Mississippi River on or about May 8, 1541. This painting depicts the splendidly dressed De Soto riding a white horse as he viewed that River at a point below Natchez. The principal objective of the expedition was to find silver and gold in the new world. There is some disagreement on the actual landing site of the expedition on the west coast of La Florida. However, the most commonly cited site is south Tampa Bay near Manatee although Charlotte Harbor and San Carlos Bay have also been cited as possibilities. From that location, De Soto launched an extended land-based trek to locate silver and gold. This journey ultimately led De Soto westward to the Mississippi River and his death of fever on the west bank of the river on May 21, 1542. The illustration represents a consensus-based reconstruction of De Soto’s route. Prior to his death, De Soto designated his field commander, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, to assume command of the expedition. Leaving De Soto’s grave site on the Mississippi River, the expedition headed west and then southwest hoping to reach New Spain (Blue route on map). Lacking an interpreter and dwindling prospects for food, the expedition retraced their route back to the Mississippi River. After arriving at the river, they proceeded to build seven bergantines that they sailed down the river and into the Gulf (Green route on mappartial). Following the coasts of Louisiana and Texas, they arrived at the Panuco River (located approximately at the “x” on the map) some 53 days later with 322 soldiers of the original contingent of 600. The De Soto- de Moscoso expedition is considered to be the first major exploration of the interior of the North American continent. A positive attribute of the expedition is that it provided some of the earliest observations of Native American peoples. A possible negative consequence is that the expedition likely introduced European diseases into the Native America population that proved to be devastating, resulting in many deaths. The drawing below shows the Alvarado fleet anchored at the mouth of the Panuco River.

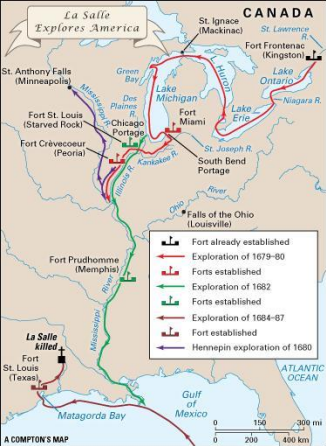

1684- Rene-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle, supported by a grant from Louis XIV, led an expedition whose purpose was to establish a French colony near the mouth of the Mississippi River that among other purposes would serve as a base for launching attacks against the Spanish forces in Mexico. He specifically planned to locate the colony near the villages of the Taensa Indians on Lake St. Joseph in what is now Tensas Parish, Louisiana. An important component of the voyage was to locate and document the mouth of the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico. The expedition consisted of four ships and 300 colonists. Preceding this voyage and during the period, 1679-1680, La Salle explored several of the Great Lakes and northern tributaries to the Mississippi River but in 1682 canoed to the mouth of the Mississippi River from the Illinois River and claimed the lands of the Mississippi River basin for France naming the lands La Louisiane in honor of Louis XIV and placing a marker. I found one source that suggested that the marker was placed at the mouth of South Pass but such a claim has not been universally validated. This painting (c1870 by French lithographer Jean-Adolphe Bocquin) portrays a depiction of the ceremony claiming these lands for France but the accuracy of its representation of the actual event is suspect. Returning to the 1684 voyage, La Salle set out on July 24th from La Rochelle France with a contingent of four ships and the 300 or so colonists noted earlier. Problems beset the expedition from the outset including ship maintenance issues, dissension among its leaders, pirates, illness, and poor navigation.

Having failed to locate a pass to the Mississippi River and now a contingent of only one ship and 180 individuals, the expedition established a settlement on a bay on Garcitas Creek near the vicinity of present-day Victoria, Texas. From that location, La Salle lead three expeditions on foot eastward to locate the mouth of the Mississippi River but failed on each occasion. During that period, the last remaining ship in the expedition, La Belle, ran aground in the bay and sank. In 1687, presumably disenchanted with La Salle’s leadership, a member of the expedition, Pierre Duhaut, ambushed and killed La Salle. In retribution, James Hiems avenged La Salle’s death by killing Haut. This action and the confusion that followed resulted in other members of the expedition being killed.

The settlement was attacked in 1688 by members of a native tribe that resulted in the killing of the 20 adults. However, it is reported that 10 adults somehow escaped the massacre and were able to live among Native American tribes. In addition, five children were taken captive. The reasons for the population dwindling from a reported 180 in 1684 to less than 40 in 1688 are unclear but likely attributable to disease and the killings of 1687 surrounding La Salle’s assassination. At some undefined date, all the survivors were captured and released by the Spanish. Six or only 2 percent of the original La Salle expedition of 300 individuals made their way to Canada after being released by the Spanish and ultimately back to France.

1699-1702- d’Iberville and d’Bienville. Fundamental to the history of Louisiana and New Orleans are the exploits and discoveries of Peter LeMoyne d’Iberville (on the left) and JeanBaptist LeMoyne d’Bienville (on the right) from three Gulf voyages during the period 1699-1702. D’Iberville’s translated Gulf Journals provide his first-hand account of actions and observations for each of his voyages. Of particular interest is his account of the voyage of 1699 in The Journal of the Badine. The Badine was the ship, reported to be a small frigate, commanded by d'Iberville for the 1699 voyage. The Badine was accompanied by another frigate, the Marin. The purpose of the voyage dates back to 1684 at which time French King Louis XIV sent Rene’- Robert Cavelier sieur de La Salle to the Mississippi Valley to:

1) Establish a colony to control the fur trade and provide a base for defense against Spanish and English encroachment and

2) Locate the mouth of the Mississippi River from the Gulf.

Not only was La Salle unsuccessful but members of his crew mutinied and killed him. Delayed by a number of factors and conditions, it was not until 1697 that Louis XIV could again direct efforts to achieve his original intent to establish a colony on the Mississippi River and locate the Gulf of Mexico outlet of the river. However, it took almost two years to mount a new attempt to achieve the original goals of the La Salle expedition. D’Iberville, who had established himself as a “fighting man”, was selected for this endeavor. Phillip Phelypeaux, Comite de Pontchartrain, French Minister of Marine, gave d’Iberville the charge to go to the Gulf of Mexico, locate the mouth of the Mississippi River, and select a good site that could be defended by a few men to block entry to the river by other nations.

D’Iberville departed France in October 1698 with four ships and sighted land on the northern Gulf Coast on January 24, 1699, that he identified as “sand dunes which look very white.” He then proceeded westward and on January 26 th noted two ships anchored on what he recorded as a lake but in reality was Pensacola Bay. The officer that d’Iberville sent to make contact with those onboard the ships learned that a contingent of some three hundred Spanish men were engaged in building a shore fortification. After some negotiations, the Spanish commandant in charge granted d’Iberville’s wishes for supplies of water and wood but would not agree to allow the fleet to enter and anchor in the bay.

Having been denied entrance to Pensacola Bay, d’Iberville’s fleet got underway on January 30th heading westward while more or less paralleling the coast. Several days later he anchored off the entrance to Mobile Bay and sent out contingents of his men to determine if an eastern branch of the Mississippi River might empty into the bay. Of course, no such branch was found. D’Iberville then again proceeded westward until finding a safe anchorage on February 10th on the northside of Ship Island in the Mississippi Sound that could be used as a base for his mission to find an entrance to and explore the Mississippi River. However, before launching this effort, he engaged with the Native American tribes in the area in an attempt to gain as much guidance as possible before proceeding. For the expedition, d’Iberville chose to proceed in longboats and canoes that could be rowed or paddled, respectively. The party set out on February 26th , exploring the coastline inside the Chandeleur Islands as they proceeded westward. Continuing westward, the expedition experienced severe storm conditions on March 2nd. Faced with these dire circumstances, d’Iberville made the decision to “run ashore” lest he and his men perish at sea. Blocking the shoreline were what appeared to be “rocks” but were later identified as logs petrified by the mud. Luckily, as their boats drew closer to the shore, an opening in the “rocks” came into view- an entrance to the Mississippi River! Rowing and paddling against the river current, D’Iberville and his men proceeded northward, interacting in a friendly manner along the way with Native American tribes. Their travels extended as far north as the region of the Old River at which point they turned around and began their return journey on March 22nd . On the 24th, they reached the waterway that they had been told by members of one of the Native American tribes would provide them with a shorter route to their ships anchored in the Mississippi Sound.

Using the guidance from local Native American tribes, d’Iberville navigated Bayou Manchac from the Mississippi River naming it River d’Iberville and then exiting first into one body of water naming it Lake Maurepas and then into a second, naming it Lake Pontchartrain. Again, based on guidance he had received from Native Americans, d’Iberville continued across Lake Pontchartrain to pass through the Rigolets into the Mississippi Sound to reconnect with his fleet Having not identified a good settlement site during his exploration of the Mississippi River, he left a garrison of 81 men to establish Fort Maurepas near what is now Ocean Springs, MS, naming his brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville second in command. He returned to France only to lead a second expedition to the Gulf Coast and the Mississippi River, leaving France in October 1699 and arriving at Fort Maurepas in January 1700. At his brother’s urging, during this expedition he directed the establishment of a second “Fort Maurepas” at a site selected by his brother near the present town of Phoenix in Plaquemine Parish. This fort, located approximately at the “x” on the graphic, was referred to as Fort De La Bouylaye or Fort Mississippi and is considered to be the first European settlement in present day Louisiana. On his third voyage to the northern Gulf Coast in 1702, d’Iberville oversaw the transfer of the seat of French colonial government from Fort Maurepas to and development of a new Mobile settlement somewhat north of the present-day City of Mobile.

In an effort to limit this brief to a reasonable length, many details concerning the exploits of d’Iberville and d’Bienville have been excluded. However, a comprehensive coverage of their exploits will be provided in a future brief.

References

Bienville’s Dilemma, Richard Campanella, Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2008.

Iberville’s Gulf Journals, Translated and Edited by Richebourg Gaillard McWilliams, The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 1981.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9-Robert_Cavelier,_Sieur_de_La_Salle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hernando_de_Soto

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narv%C3%A1ez_expedition

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alonso_%C3%81lvarez_de_Pineda